Alternating current

Alternating current

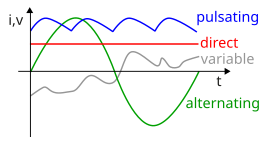

Alternating current (AC) is an electric current which periodically reverses direction, in contrast to direct current (DC) which flows only in one direction. Alternating current is the form in which electric power is delivered to businesses and residences, and it is the form of electrical energy that consumers typically use when they plug kitchen appliances, televisions, fans and electric lamps into a wall socket. A common source of DC power is a battery cell in a flashlight. The abbreviations AC and DC are often used to mean simply alternating and direct, as when they modify current or voltage.[1][2]

The usual waveform of alternating current (ac) in most electric power circuits is a sine wave. In certain applications, different waveforms are used, such as triangular or square waves. Audio and radio signals carried on electrical wires are also examples of alternating current. These types of alternating current carry information such as sound (audio) or images (video) sometimes carried by modulation of an AC carrier signal. These currents typically alternate at higher frequencies than those used in power transmission.

Transmission, distribution, and domestic power supply.

A schematic representation of long distance electric power transmission. C=consumers, D=step down transformer, G=generator, I=current in the wires, Pe=power reaching the end of the transmission line, Pt=power entering the transmission line, Pw=power lost in the transmission line, R=total resistance in the wires, V=voltage at the beginning of the transmission line, U=step up transformer.

Electrical energy is distributed as alternating current because AC voltage may be increased or decreased with a transformer. This allows the power to be transmitted through power lines efficiently at high voltage, which reduces the energy lost as heat due to resistance of the wire, and transformed to a lower, safer, voltage for use. Use of a higher voltage leads to significantly more efficient transmission of power. The power losses ({\displaystyle P_{\rm {w}}}) in the wire are a product of the square of the current (I) and the resistance (R) of the wire, described by the formula

- {\displaystyle P_{\rm {w}}=I^{2}R\,.}

This means that when transmitting a fixed power on a given wire, if the current is halved (i.e. the voltage is doubled), the power loss will be four times less.

The power transmitted is equal to the product of the current and the voltage (assuming no phase difference); that is,

- {\displaystyle P_{\rm {t}}=IV\,.}

Consequently, power transmitted at a higher voltage requires less loss-producing current than for the same power at a lower voltage. Power is often transmitted at hundreds of kilovolts, and transformed to 100 V – 240 V for domestic use.

High voltage transmission lines deliver power from electric generation plants over long distances using alternating current. These lines are located in eastern Utah.

High voltages have disadvantages, such as the increased insulation required, and generally increased difficulty in their safe handling. In a power plant, energy is generated at a convenient voltage for the design of a generator, and then stepped up to a high voltage for transmission. Near the loads, the transmission voltage is stepped down to the voltages used by equipment. Consumer voltages vary somewhat depending on the country and size of load, but generally motors and lighting are built to use up to a few hundred volts between phases. The voltage delivered to equipment such as lighting and motor loads is standardized, with an allowable range of voltage over which equipment is expected to operate. Standard power utilization voltages and percentage tolerance vary in the different mains power systems found in the world. High-voltage direct-current (HVDC) electric power transmission systems have become more viable as technology has provided efficient means of changing the voltage of DC power. Transmission with high voltage direct current was not feasible in the early days of electric power transmission, as there was then no economically viable way to step down the voltage of DC for end user applications such as lighting incandescent bulbs.

Three-phase electrical generation is very common. The simplest way is to use three separate coils in the generator stator, physically offset by an angle of 120° (one-third of a complete 360° phase) to each other. Three current waveforms are produced that are equal in magnitude and 120° out of phase to each other. If coils are added opposite to these (60° spacing), they generate the same phases with reverse polarity and so can be simply wired together. In practice, higher “pole orders” are commonly used. For example, a 12-pole machine would have 36 coils (10° spacing). The advantage is that lower rotational speeds can be used to generate the same frequency. For example, a 2-pole machine running at 3600 rpm and a 12-pole machine running at 600 rpm produce the same frequency; the lower speed is preferable for larger machines. If the load on a three-phase system is balanced equally among the phases, no current flows through the neutral point. Even in the worst-case unbalanced (linear) load, the neutral current will not exceed the highest of the phase currents. Non-linear loads (e.g. the switch-mode power supplies widely used) may require an oversized neutral bus and neutral conductor in the upstream distribution panel to handle harmonics. Harmonics can cause neutral conductor current levels to exceed that of one or all phase conductors.

For three-phase at utilization voltages a four-wire system is often used. When stepping down three-phase, a transformer with a Delta (3-wire) primary and a Star (4-wire, center-earthed) secondary is often used so there is no need for a neutral on the supply side. For smaller customers (just how small varies by country and age of the installation) only a single phase and neutral, or two phases and neutral, are taken to the property. For larger installations all three phases and neutral are taken to the main distribution panel. From the three-phase main panel, both single and three-phase circuits may lead off. Three-wire single-phase systems, with a single center-tapped transformer giving two live conductors, is a common distribution scheme for residential and small commercial buildings in North America. This arrangement is sometimes incorrectly referred to as “two phase”. A similar method is used for a different reason on construction sites in the UK. Small power tools and lighting are supposed to be supplied by a local center-tapped transformer with a voltage of 55 V between each power conductor and earth. This significantly reduces the risk of electric shock in the event that one of the live conductors becomes exposed through an equipment fault whilst still allowing a reasonable voltage of 110 V between the two conductors for running the tools.

A third wire, called the bond (or earth) wire, is often connected between non-current-carrying metal enclosures and earth ground. This conductor provides protection from electric shock due to accidental contact of circuit conductors with the metal chassis of portable appliances and tools. Bonding all non-current-carrying metal parts into one complete system ensures there is always a low electrical impedance path to ground sufficient to carry any fault current for as long as it takes for the system to clear the fault. This low impedance path allows the maximum amount of fault current, causing the overcurrent protection device (breakers, fuses) to trip or burn out as quickly as possible, bringing the electrical system to a safe state. All bond wires are bonded to ground at the main service panel, as is the neutral/identified conductor if present.

AC power supply frequencies.

The frequency of the electrical system varies by country and sometimes within a country; most electric power is generated at either 50 or 60 Hertz. Some countries have a mixture of 50 Hz and 60 Hz supplies, notably electricity power transmission in Japan. A low frequency eases the design of electric motors, particularly for hoisting, crushing and rolling applications, and commutator-type traction motors for applications such as railways. However, low frequency also causes noticeable flicker in arc lamps and incandescent light bulbs. The use of lower frequencies also provided the advantage of lower impedance losses, which are proportional to frequency. The original Niagara Falls generators were built to produce 25 Hz power, as a compromise between low frequency for traction and heavy induction motors, while still allowing incandescent lighting to operate (although with noticeable flicker). Most of the 25 Hz residential and commercial customers for Niagara Falls power were converted to 60 Hz by the late 1950s, although some[which?] 25 Hz industrial customers still existed as of the start of the 21st century. 16.7 Hz power (formerly 16 2/3 Hz) is still used in some European rail systems, such as in Austria, Germany, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland. Off-shore, military, textile industry, marine, aircraft, and spacecraft applications sometimes use 400 Hz, for benefits of reduced weight of apparatus or higher motor speeds. Computer mainframe systems were often powered by 400 Hz or 415 Hz for benefits of ripple reduction while using smaller internal AC to DC conversion units.[3] In any case, the input to the M-G set is the local customary voltage and frequency, variously 200 V (Japan), 208 V, 240 V (North America), 380 V, 400 V or 415 V (Europe), and variously 50 Hz or 60 Hz.

Effects at high frequencies.

A Tesla coil producing high-frequency current that is harmless to humans, but lights a fluorescent lamp when brought near it

A direct current flows uniformly throughout the cross-section of a uniform wire. An alternating current of any frequency is forced away from the wire’s center, toward its outer surface. This is because the acceleration of an electric charge in an alternating current produces waves of electromagnetic radiation that cancel the propagation of electricity toward the center of materials with high conductivity. This phenomenon is called skin effect. At very high frequencies the current no longer flows in the wire, but effectively flows on the surface of the wire, within a thickness of a few skin depths. The skin depth is the thickness at which the current density is reduced by 63%. Even at relatively low frequencies used for power transmission (50 Hz – 60 Hz), non-uniform distribution of current still occurs in sufficiently thick conductors. For example, the skin depth of a copper conductor is approximately 8.57 mm at 60 Hz, so high current conductors are usually hollow to reduce their mass and cost. Since the current tends to flow in the periphery of conductors, the effective cross-section of the conductor is reduced. This increases the effective AC resistance of the conductor, since resistance is inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area. The AC resistance often is many times higher than the DC resistance, causing a much higher energy loss due to ohmic heating (also called I2R loss).

Techniques for reducing AC resistance.

For low to medium frequencies, conductors can be divided into stranded wires, each insulated from one another, and the relative positions of individual strands specially arranged within the conductor bundle. Wire constructed using this technique is called Litz wire. This measure helps to partially mitigate skin effect by forcing more equal current throughout the total cross section of the stranded conductors. Litz wire is used for making high-Q inductors, reducing losses in flexible conductors carrying very high currents at lower frequencies, and in the windings of devices carrying higher radio frequency current (up to hundreds of kilohertz), such as switch-mode power supplies and radio frequency transformers.

Techniques for reducing radiation loss.

As written above, an alternating current is made of electric charge under periodic acceleration, which causes radiation of electromagnetic waves. Energy that is radiated is lost. Depending on the frequency, different techniques are used to minimize the loss due to radiation.

Twisted pairs.

At frequencies up to about 1 GHz, pairs of wires are twisted together in a cable, forming a twisted pair. This reduces losses from electromagnetic radiation and inductive coupling. A twisted pair must be used with a balanced signalling system, so that the two wires carry equal but opposite currents. Each wire in a twisted pair radiates a signal, but it is effectively cancelled by radiation from the other wire, resulting in almost no radiation loss.

Coaxial cables.

Coaxial cables are commonly used at audio frequencies and above for convenience. A coaxial cable has a conductive wire inside a conductive tube, separated by a dielectric layer. The current flowing on the surface of the inner conductor is equal and opposite to the current flowing on the inner surface of the outer tube. The electromagnetic field is thus completely contained within the tube, and (ideally) no energy is lost to radiation or coupling outside the tube. Coaxial cables have acceptably small losses for frequencies up to about 5 GHz. For microwave frequencies greater than 5 GHz, the losses (due mainly to the electrical resistance of the central conductor) become too large, making wave guides a more efficient medium for transmitting energy. Coaxial cables with an air rather than solid dielectric are preferred as they transmit power with lower loss.

Wave guides.

Waveguides are similar to coaxial cables, as both consist of tubes, with the biggest difference being that the waveguide has no inner conductor. Waveguides can have any arbitrary cross section, but rectangular cross sections are the most common. Because waveguides do not have an inner conductor to carry a return current, waveguides cannot deliver energy by means of an electric current, but rather by means of a guided electromagnetic field. Although surface currents do flow on the inner walls of the waveguides, those surface currents do not carry power. Power is carried by the guided electromagnetic fields. The surface currents are set up by the guided electromagnetic fields and have the effect of keeping the fields inside the waveguide and preventing leakage of the fields to the space outside the waveguide. Waveguides have dimensions comparable to the wavelength of the alternating current to be transmitted, so they are only feasible at microwave frequencies. In addition to this mechanical feasibility, electrical resistance of the non-ideal metals forming the walls of the waveguide cause dissipation of power (surface currents flowing on lossy conductors dissipate power). At higher frequencies, the power lost to this dissipation becomes unacceptably large.

Fiber optics.

At frequencies greater than 200 GHz, waveguide dimensions become impractically small, and the ohmic losses in the waveguide walls become large. Instead, fiber optics, which are a form of dielectric waveguides, can be used. For such frequencies, the concepts of voltages and currents are no longer used.